Why Your MIDI Drums Sound “Impossible” (And How to Fix It)

Physical Limits: Why Your MIDI Drums Sound “Impossible” (And How to Fix It)

Let me tell you about the most embarrassing moment of my production career.

I’d been working on this hard rock track in Cubase (using Superior 3 as the virtual drum instrument) for weeks. The drums were tight—or so I thought. I sent it to a drummer friend for feedback, fully expecting him to be impressed.

His response? “Dude… how many arms does your drummer have?”

I listened back. He was right. At the 2:15 mark, I had programmed simultaneous hits on the ride cymbal, crash cymbal, floor tom, and hi-hat—all while the kick and snare were going. Unless my imaginary drummer was an octopus, this pattern was physically impossible.

And once you hear it, you can’t unhear it.

This is one of the fastest ways to destroy the credibility of an otherwise professional track: programming drum patterns that defy the basic laws of physics and human anatomy. Your samples might be pristine, your mix might be perfect, but if you’ve got a drummer pulling off moves that would require teleportation or extra limbs, everyone with even basic musical training is going to notice.

The good news? This is completely fixable once you understand the physical limitations of real drummers. Let’s break down the rules that separate believable MIDI programming from “yeah, a computer definitely made this.”

The Four-Limb Rule: Basic Math for Believable Drums

Here’s the fundamental truth that every MIDI programmer needs tattooed on their brain:

Drummers have exactly four limbs. Two hands. Two feet. That’s it.

This sounds stupidly obvious, right? But you’d be shocked how many MIDI patterns violate this basic principle. I’ve heard countless bedroom productions where someone hits five or six things simultaneously, apparently unaware that human beings haven’t evolved extra appendages since we started making beats.

The Maximum Simultaneous Hit Count

At any given moment, a drummer can strike a maximum of four things—and that’s only if they’re playing doubles with both hands and both feet, which is actually pretty rare outside of extreme metal. More realistically, most patterns max out at two or three simultaneous hits:

Common two-hit combinations:

- Kick + snare

- Kick + hi-hat/ride

- Crash + kick (classic downbeat)

- Floor tom + ride (common in fills)

Common three-hit combinations:

- Kick + snare + hi-hat (the backbone of most grooves)

- Crash + floor tom + kick (big fill ending)

- Ride + snare + kick (jazz/funk patterns)

Rare four-hit combinations:

- Double bass + both hands on different cymbals/drums

- Only really happens in technical metal or fusion

- If you’re programming this, you better have a damn good reason

The Quick Test

Pull up your MIDI piano roll right now. Look at any vertical line. Count how many notes hit at exactly the same time. If you see more than four, you’ve broken physics. If you see four, ask yourself: “Is this a double-bass pattern or am I just being lazy?”

The “Crash Cymbal Crime”

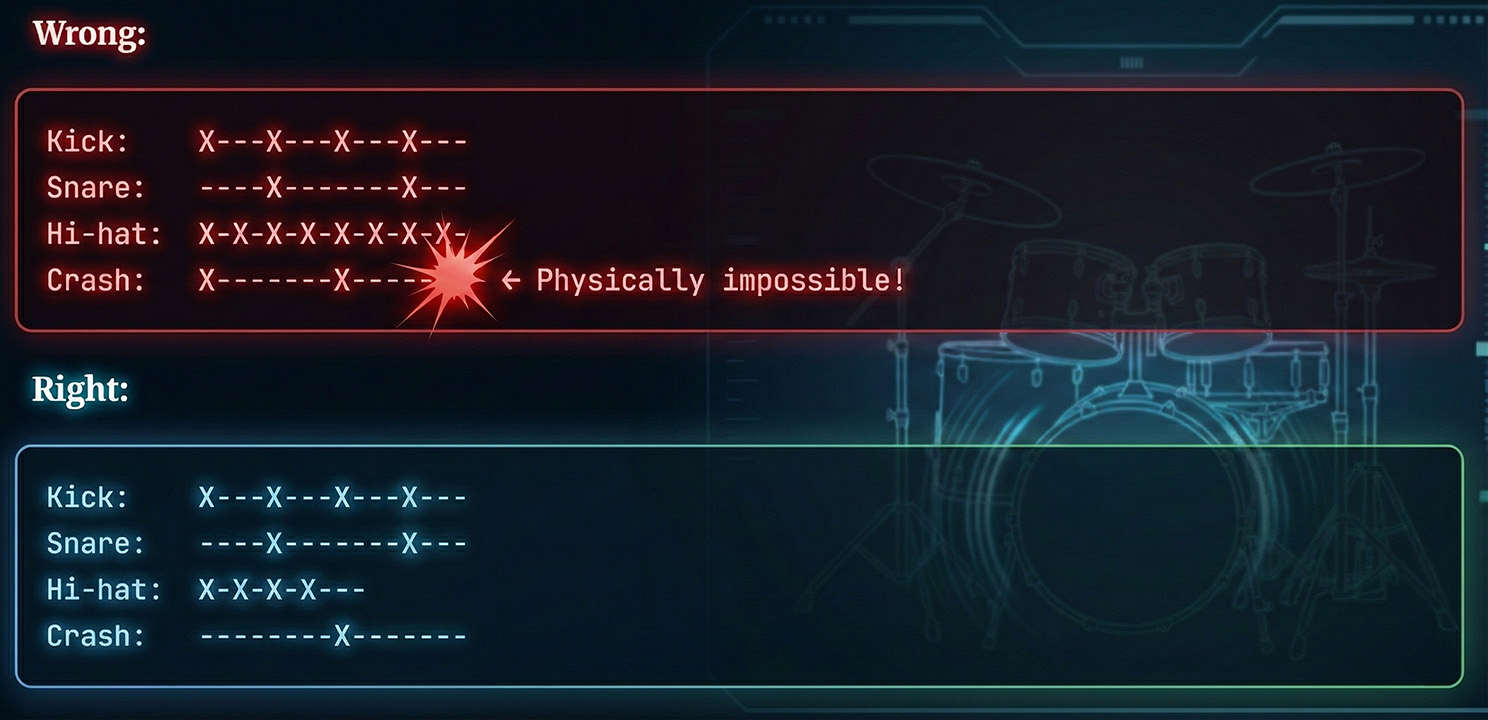

This is the most common violation I see: someone programs a crash cymbal hit while also keeping the hi-hat going.

Think about a drummer’s physical setup for a second. The hi-hat is played with the right hand (for right-handed drummers, which is most of them). The crash cymbal is also typically played with the right hand. Unless this drummer has mastered bilocation, they can’t hit both simultaneously while maintaining a consistent hi-hat pattern.

See the difference? When the crash hits, the hi-hat pauses because the same hand can’t be in two places at once.

Hi-Hat Mechanics: Understanding Choke Groups

Let’s get deeper into hi-hat physics, because this is where a lot of MIDI programming falls apart.

Hi-hats aren’t just a single instrument—they’re two cymbals on a stand controlled by a foot pedal. This creates three distinct sounds:

- Closed hi-hat: Foot down, cymbals pressed together, tight “chick” sound

- Open hi-hat: Foot up, cymbals separated, sustained “tshhh” sound

- Pedal hi-hat: Foot stomps down, creating a “chick” sound without stick hits

Here’s the critical thing MIDI programmers miss: these sounds are mutually exclusive. When a drummer closes the hi-hat, they physically stop the open hi-hat sound. The cymbals clamp together, cutting off the ring instantly.

What Are Choke Groups?

In your sampler or drum plugin, choke groups (sometimes called “mute groups”) tell the software: “If sound A plays, immediately cut off sound B.” This mimics the physical behavior of real cymbals.

Most decent drum VSTs have this programmed in automatically. But if you’re building your own kit from samples or using certain older plugins, you might need to set this up manually. Otherwise, you get this disaster:

Without choke groups: You play an open hi-hat, and it rings out for 2 seconds. Then you play a closed hi-hat on the next beat. But the open hi-hat is still ringing underneath it. The result? A muddy, amateurish mess that screams “I don’t understand how drums work.”

With choke groups: You play an open hi-hat, it rings, then the closed hi-hat cuts it off immediately—just like real cymbals would. Clean, professional, believable.

Programming Realistic Hi-Hat Patterns

When programming hi-hats, think about the pedal position:

- 8th note patterns: Usually all closed (foot stays down)

- 16th note patterns: Mix of closed and slightly open (foot bounces, creating variation)

- Groove patterns: Intentional open hats on specific beats for accent

- Transitions: Open hat into closed creates punctuation

Here’s a typical rock/pop hi-hat pattern that sounds human:

Beat: 1 e + a 2 e + a 3 e + a 4 e + a

Closed: X X X X - X X X X X X X - X X X

Open: - - - - X - - - - - - - X - - -

Notice how the open hats replace closed hats on the “+” of 2 and 4? That’s physically accurate. The drummer lifts their foot, plays the open hat, then closes it again for the next hit.

The Pedal Hat Secret

Want to know a secret that separates pro-sounding programmed drums from amateur hour? Pedal hi-hats.

Most MIDI programmers completely ignore the pedal hat (that “chick” sound from stomping the pedal without hitting with a stick). Real drummers use it constantly—especially on beats 2 and 4 in conjunction with the snare, or as ghost notes between stick hits.

Try adding quiet pedal hat hits (velocity around 40-60) on the 8th or 16th notes between your main hi-hat pattern. It adds rhythmic glue and makes the whole pattern feel more connected, like there’s an actual foot working that pedal.

Stick Physics: The Geography of Movement

Here’s something most MIDI programmers never think about: drums take up physical space, and drummers have to move their hands through that space to hit them.

A standard drum kit layout looks roughly like this (from the drummer’s perspective):

Crash Ride

| |

HH Tom Tom Floor Tom

| | | |

Snare

|

Hi-hat pedal Kick

When a drummer plays a fill that moves across the kit—say, from the high tom to the floor tom—their hands have to physically travel that distance. This takes time.

The Latency of Movement

Let’s say you program a fill like this:

High tom: X---

Mid tom: -X--

Floor tom: --X-

Crash: ---X

That looks fine in the piano roll, with each hit exactly one 16th note apart. But in reality, a drummer playing this would need to:

- Strike the high tom (right hand)

- Move right hand 8-12 inches to mid tom

- Strike mid tom

- Move right hand another 10-14 inches to floor tom

- Strike floor tom

- Move right hand 18-24 inches up and across to crash cymbal

- Strike crash

At fast tempos, this can become literally impossible without the hits blurring together or being rushed. At moderate tempos, you need to account for the acceleration and deceleration of the stick as it moves between drums.

The Solution: Strategic Micro-Timing

When programming fills that move across the kit, don’t keep everything robotically locked to the grid. Add 3-8 milliseconds of delay to hits that require larger physical movements, especially:

- Moving from toms to cymbals (big distance)

- Alternating between high tom and floor tom (skipping the middle)

- Any pattern that crosses from left side to right side of the kit

Unrealistic (all perfectly on-grid):

Time: 0ms 125ms 250ms 375ms

High tom: X

Mid tom: X

Floor tom: X

Crash: X

Realistic (accounting for movement):

Time: 0ms 128ms 256ms 388ms

High tom: X

Mid tom: X

Floor tom: X

Crash: X

See those tiny timing adjustments? They’re subtle, but they make the difference between a fill that sounds mechanical and one that sounds like an actual human played it.

The “Crossed Hands” Paradox

Here’s a trap I see all the time: someone programs a pattern where the left hand would need to play the hi-hat while the right hand plays the snare.

In standard drumming technique:

- Right hand: Hi-hat and ride cymbal (also crashes)

- Left hand: Snare drum (also toms during fills)

When you program rapid hi-hat and snare patterns, you need to think about whether a drummer’s hands could actually pull this off, or if they’d need to cross their arms in weird ways.

This pattern is fine:

Hi-hat: X-X-X-X-X-X-X-X-

Snare: ----X-------X---

Right hand handles hi-hat, left hand just comes in for snare backbeats. Easy.

This pattern is problematic:

Hi-hat: X-X-X-X-X-X-X-X-

Snare: --X-X-X-X-X-X-X-

Now the left hand has to machine-gun the snare while the right hand maintains constant 8ths on the hi-hat? That’s Travis Barker-level difficulty, and even he would probably play this differently.

The “Three Cymbals at Once” Red Flag

Let’s talk about one of the most egregious violations I see in MIDI programming: hitting multiple cymbals simultaneously.

Picture a standard drum kit setup. You’ve got:

- Hi-hats (far left)

- Crash cymbal (left-center, above high tom)

- Ride cymbal (far right)

- Maybe a second crash (right side)

These are spread across a 4-5 foot span. A drummer has two hands.

So when I hear someone hit the crash, ride, AND a china cymbal all at the exact same moment, I know immediately: “Computer made this.”

The One-Hand, One-Cymbal Rule

At any given instant, each hand can only strike one cymbal. That means:

- Maximum two cymbals can crash together simultaneously

- If you want a big “everything at once” crash, it’s typically crash + ride

- Three cymbals? Physically impossible with two hands

- Four cymbals? Now you’re just trolling

Exception: Some drummers do set up cymbals close enough to strike two with one hand (like a splash stacked on a crash), but this creates a single blended sound, not two distinct hits. And it’s rare enough that if you’re doing it in your MIDI programming, you should know exactly why.

The Aftermath of a Crash

Here’s another subtle detail: after a drummer crashes a cymbal with their right hand, that hand is occupied for a split second. They can’t immediately return to the hi-hat or ride pattern without a tiny gap.

Watch any live drummer. When they crash, the underlying pattern (usually hi-hat or ride) pauses for a 16th or 32nd note. Then it resumes. This pause is necessary because physics doesn’t allow instant teleportation back to the previous position.

If your MIDI has crash cymbals happening while the hi-hat pattern continues uninterrupted in perfect 16th notes? Dead giveaway.

Real-World Examples: Good vs. Bad

Let’s look at some common MIDI programming scenarios and diagnose what’s wrong (or right).

Example 1: The Impossible Intro

The MIDI:

Kick: X-------X-------

Snare: ----X-------X---

Hi-hat: X-X-X-X-X-X-X-X-

Ride: X-X-X-X-X-X-X-X- ← PROBLEM!

Crash: X-------X------- ← BIGGER PROBLEM!

The Issue: The right hand cannot simultaneously play hi-hat, ride, AND crash. This would require three arms, or hand-cloning technology.

The Fix:

Kick: X-------X-------

Snare: ----X-------X---

Ride: X-X-X-X-X---X-X- ← Ride pauses when crash hits

Crash: --------X-------

Example 2: The Busy Fill

The MIDI:

Beat: 1 e + a 2 e + a

High tom: X X

Mid tom: X X

Floor tom: X X

Crash: X X ← PROBLEM!

Ride: X X ← PROBLEM!

The Issue: Crash and ride hitting together on every 16th note at the end? That’s both hands committed to cymbals while somehow the toms were just played. Time paradox.

The Fix:

Beat: 1 e + a 2 e + a

High tom: X -

Mid tom: - X X

Floor tom: - X X

Crash: X ← Single crash to end

Much cleaner, much more believable.

How to Train Your Ear (And Your MIDI Editor)

The best way to avoid these mistakes? Study real drummers.

Action steps:

- Watch live drum videos on YouTube. Not for entertainment—for education. Watch where the drummer’s hands are. Notice when they move, when they can’t possibly hit two things at once, when patterns pause for crashes.

- Load up actual drum recordings. Programs like Superior Drummer or the vast collection at Slam Tracks give you professionally recorded, real drummer performances. Pull them into your DAW and look at the MIDI (if available) or the waveform. See where hits actually land. Notice the impossibility of certain combinations.

- Air drum your patterns. Seriously. Sit at your desk and physically mime playing what you’ve programmed. If your hands can’t do it while air drumming, a real drummer can’t do it either.

- Use the “four-limb highlight test.” In your MIDI editor, highlight every note at a single point in time. Count them. More than four? Problem. Four and it’s not a double-bass metal pattern? Probably still a problem.

When to Break the Rules (Carefully)

Look, I’m not saying you can never program physically impossible drums. Electronic music sometimes benefits from superhuman patterns—that’s part of the appeal.

But here’s the key: break these rules intentionally, not accidentally.

If you’re making glitchy IDM or experimental electronic music where the point is to sound futuristic and impossible, go nuts. Program eight-handed drum monsters. Make patterns that would require cyborg drummers from the year 3000.

But know that you’re making that choice for aesthetic reasons, not because you didn’t realize it was impossible.

The difference between “cool intentional impossible drums” and “oops I don’t understand physics” comes down to context and execution:

Intentional impossibility:

- The rest of the track is clearly electronic/experimental

- The impossible elements are featured, not accidental

- You’re using the impossibility for musical effect

- Everything else still follows physical logic where appropriate

Accidental impossibility:

- You’re making boom-bap hip-hop or rock with realistic drum sounds

- The impossible moments stick out as mistakes, not features

- You didn’t realize they were impossible

- The whole pattern has multiple physical violations

The Shortcut: Learn from Reality

Here’s the honest truth: the easiest way to avoid all these problems is to start with actual drummer performances.

You can spend hours studying drum technique, memorizing kit layouts, calculating movement latency, and manually fixing MIDI… or you can work with loops that were actually played by humans in the first place.

This is why, after two decades of recording drummers at Slam Tracks, we’ve built our entire business around live acoustic performances. Every loop in our catalog was played by a real person with exactly two hands and two feet, sitting at a real kit with physical distances between the drums. The physics is automatically correct because physics literally made it happen.

When you program MIDI, you’re trying to fake reality well enough that listeners believe it. When you use recorded loops, you’re starting with reality—then you can manipulate it however you want while maintaining that foundation of believability.

But whether you’re programming from scratch or working with pre-recorded loops, understanding these physical limitations will make you a better producer. Because even when you’re manipulating audio, you’ll make better editing choices when you understand what would or wouldn’t be possible for an actual drummer to play.

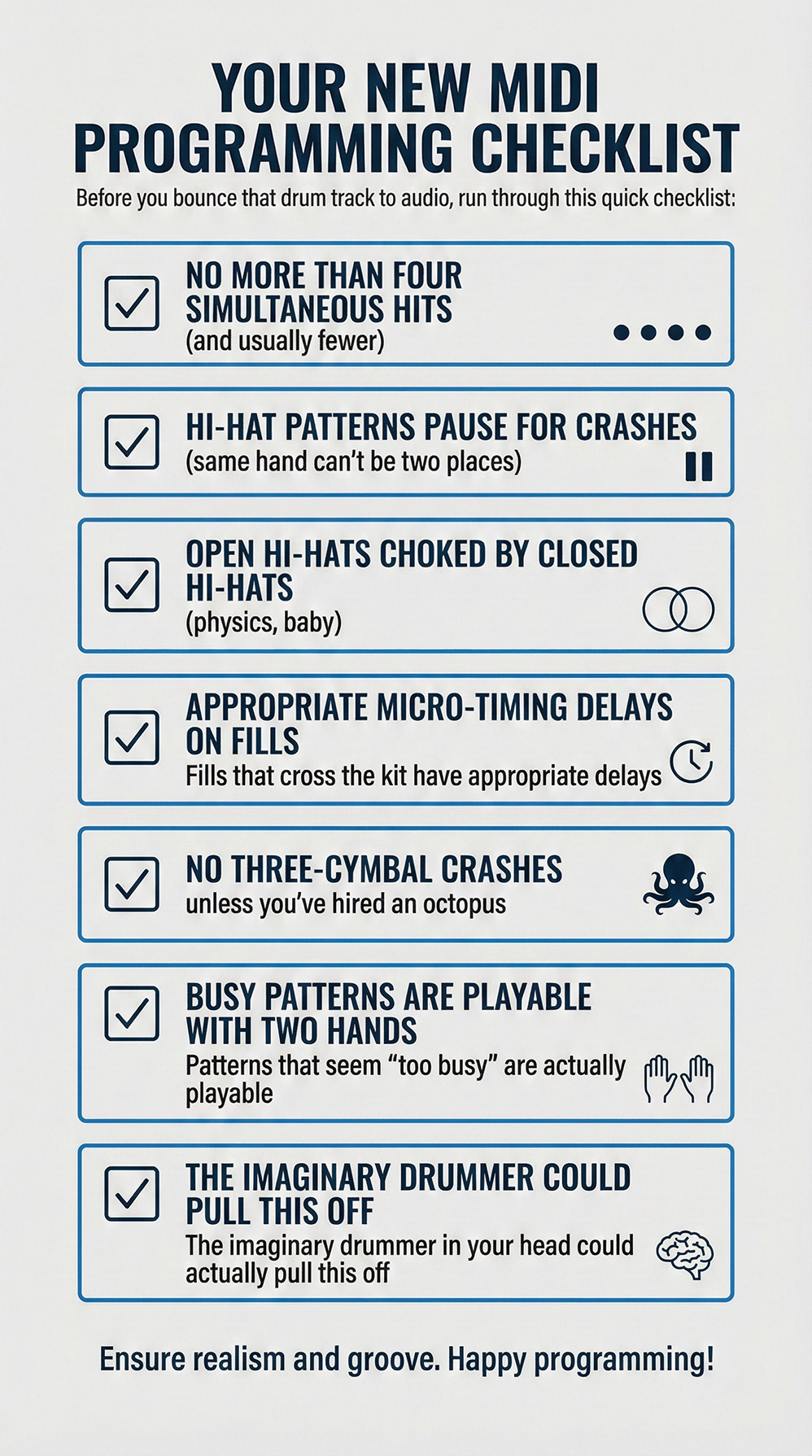

Your New MIDI Programming Checklist

Before you bounce that drum track to audio, run through this quick checklist:

- [ ] No more than four simultaneous hits at any point (and usually fewer)

- [ ] Hi-hat patterns pause when crashes happen (same hand can’t be two places)

- [ ] Open hi-hats are properly choked by closed hi-hats (physics, baby)

- [ ] Fills that cross the kit have appropriate micro-timing delays

- [ ] No three-cymbal crashes unless you’ve hired an octopus

- [ ] Patterns that seem “too busy” are actually playable with two hands

- [ ] The imaginary drummer in your head could actually pull this off

Run this checklist, fix what’s broken, and watch your programmed drums suddenly sound 10x more professional.

Because at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how good your samples are if you’re asking them to do impossible things. Physics always wins.

Now go and program drums that respect the human body. Your drum tracks and music will thank you.